Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and the Language of Massacre

On December 28, 1890, the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment intercepted a group of Lakota Native Americans en route to South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Agency and escorted them to Wounded Knee Creek, where they were instructed to make camp for the night. Historians still disagree as to what happened next but by most accounts, the cavalry surrounded the Lakota, confiscated their weapons and found themselves in a bit of a kerfuffle when a deaf Native American named Black Coyote either didn’t understand their orders or refused to give up his firearm without compensation.

“Kerfuffle,” however, is an understatement in this case. A shot was fired and within hours, at least 150 Lakota had been killed, including women and children who were pursued on horseback as they attempted to flee to safety. Some estimates place the loss of Native American life as high as 300, whereas the cavalry incurred only 25 causalities (including several resulting from friendly fire, as they’d surrounded the Lakota and shot through them).

As a professor of cultural anthropology at a community college in New Jersey, I devote a class to Wounded Knee each semester. “History textbooks used to refer to Wounded Knee as a ‘battle’,” I tell my students. “At least 20 soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor. But what does the word ‘battle’ imply?”

“That both sides were armed,” one young man replied this past spring. “That they were evenly matched,” a classmate echoed, “a battle means that there were two armies fighting against each other, not women and children, not men who’d had their guns taken away.”

We then examine a photograph of the entrance to Wounded Knee, which has been designed a National Historic Site. There’s a pale green sign with white lettering that reads “The Massacre of Wounded Knee.” Of course, it didn’t always read this way; the original version labeled it the site of a “battle” and the word “massacre” was welded on top in a literal rewriting of history.

“What does the word ‘massacre’ imply?” I ask my students. “Is a ‘massacre’ something that we want to have as part of our nation’s history?” I zoom in on the slide and tell my students to take a closer look because the sign, even in 2016, is riddled with bullet holes.

Language matters. We know that “massacres” are wrong, just as we know that “murders” are wrong, and yet we still use euphemisms like “incidents” to downplay the acts of police brutality that our country’s systemic racism continues to engender (just as we used “acts of genocide” in 1994 to downplay the atrocities then occurring in Rwanda).

On Thursday, President Obama acknowledged that the “shootings” of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were “symptomatic of a broader set of racial disparities that exist in our criminal justice system.” But he carefully referred to their deaths as an “incident,” a word which he repeated five times in his address to reference previous examples of police brutality.

He never used the word “killed,” “attacked,” or “shot,” and he certainly didn’t use the word “murdered.” Instead of “death” he used “tragedy” and “tragedies” (three times in total), thus rendering the continued loss of life somehow less embarrassing to our nation’s collective psyche.

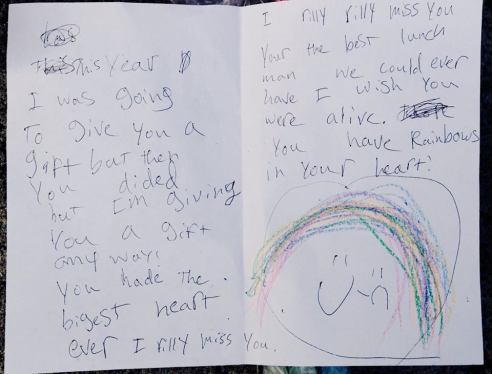

Note written by a student at the school where Philando Castile worked

A few hours later, however, he addressed the nation again, this time in response to the now “tremendous” tragedy that occurred in Dallas in which 5 police officers were killed. He didn’t mince his words this time: this was a “vicious, calculated and despicable attack on law enforcement.” There were “twisted motivations” and “senseless murders” with “no possible justification.”

I’m not faulting Obama here, at least I’m not faulting just Obama here. As our nation’s first black President, he doesn’t have much choice. He has to walk a fine line, lest he show too much allegiance to a particular group, but he’s not the only one who talks this way. These euphemisms have permeated our national dialogue: traditional media, social media, even the so-called “liberal media” who ought to know better.

I even find myself using the word “incidents” when I kick off my annual lecture on systemic racism because I know I’m going to alienate half my class if I jump right in with the truth and they’re never going to see the fallacy of “all lives matter” if they’re not even listening.

But when we sugar coat reality again and again, the message becomes clear: black lives matter, but not as much as blue lives; not as much as white lives. And until we have the courage to call a spade a spade, to admit that a “battle” is a really a “massacre” and that an “incident” is really a “murder,” our country will see this pattern play out again and again.

13 Responses to “Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and the Language of Massacre”

So lucky to have you as my daughter, you find words to encourage the examination of our society that I can only dream of…

Yeah, going through the transcripts of those two speeches really made my blood boil (I was using different search features to count how often certain words were used). I’m just mad that I haven’t been able to make it to any of the rallies here in Philly on account of my back. I did make some signs to send along to one but its hard not to feel useless right now.

Thank you for your eloquent examination of the power of language in these scenarios. Your mention of Wounded Knee reminds me of the erasure of the massacre of black citizens in Greenwood, Tulsa in 1912, which for the longest time was not even publicly acknowledged. Also thank you for “getting it,” as it often feels like people who lament “All Lives Matter” really don’t see the point. I have been largely quiet on social media just out of grief (mostly) and also anger because some of my friends just don’t seem to see the clear injustice.

Thank you, Casey. And I can’t even imagine how you must be feeling right now. It’s such maddening how many people just don’t get it and still resort to “All lives matter” or “Well, he shouldn’t have been doing X” or “what about black on black crime?” This is a systemic problem and it affects us all (to different degrees of course) and the system needs to be completely reformed.

Please do not believe you are useless when you can write so powerfully. Keep writing, keep talking, keep teaching. You frequently remind me of an archaic phrase, have you heard it? You are “a credit to your friends”, or more directly, I’m proud to know you.

Awww shucks, thanks Jill 🙂 I guess we all have our different roles to play but change just seems so incrementally slow…

This is such a powerful, well-written post. The events in America shocked the world this week — I hope that real progress is made on gun control and equality. But how long will it be until it happens again? *Sigh*

I just realized that I automatically typed ‘events’ instead of ‘murders’ — toning down the language. I think, as you say, euphemisms are so engrained in the media and our collective consciousness that we find ourselves using them without realizing. Very thought-provoking…

Right? It’s become so automatic for us all at this point to downplay the gravity of what has happened (“what has happened” being another case in point). I keep thinking of that U2 song, “One more in the name of love…”

Bless you, Kat, for all your powerful work in the world.

[…] the war on drugs has succeeded only in making us the most incarcerated nation on earth, that these “episodes” and “incidents” of police brutality keep on happening and that they keep on happening to the same types of people. […]

[…] for every Bowie, for every Prince, for every Princess, I raise you a dead Syrian. I raise you a Philando Castile, an Alton Sterling. I raise you a young woman at Standing Rock who lost her arm while peacefully resisting the […]

[…] at City Hall, I never made it to a single march or vigil. Sometimes, in class, I also found myself saying “incidents of police brutality” instead of calling a spade a fucking spade because I’m afraid to alienate my white students. This […]